Our phones register in radio cells to route the calls to the phone network. When we move around, we occasionally leave one cell and enter another. So our movements over leave a trace through the cells we have been passing the course of the day. Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye and his co-authors from MIT explored, how many observations we need, to identify a specific user. Based on actual data provided by telephone companies, they calculated, that just four observations are sufficient to identify 95% of all mobile users. We need just so little evidence because people’s moving patterns are surprisingly unique, just like our fingerprints, these are more or less reliable identifiers.

Location

When we analyze the raw data, that we collect through our mobile sensor framework ‘explore’ we found several other fingerprint-like traces, that all of us continuously drop by using our smartphones. Obviously we can reproduce de Monjoye’s experiment with much more granular resolution when we use the phone’s own location tracking data instead of the rather coarse grid of the cells. GPS and mobile positioning spot us with high precision.

Wifi

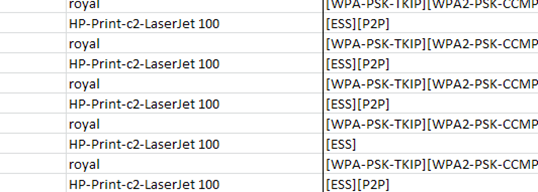

Inside buildings we have the Wifis in reception. Each Wifi has a unique identifier, the BSSID and provides lots of other useful information.

Wifis in reception around my office. When the location of the wifi emitter is known we can use signal strength to locate users within buildings.

Even the aribrary lable “SSID” can often be telling: You can immediately see what kind of printer I use.

Magnetic fields

To provide compass functionality, most smartphones carry a magnetic flux sensor. This probe monitors the surrounding magnetic fields in all three dimensions.

Each location has its very own magnetic signature. Also many things we do leave telling magnetic traces – like driving a car or riding on a train. In this diagram you see my magnetic readings. You can immediately detect when I was home or when I was traveling.

Battery

The way we use the phone has effect on the power consumptions. This can be monitored via the battery charge probe:

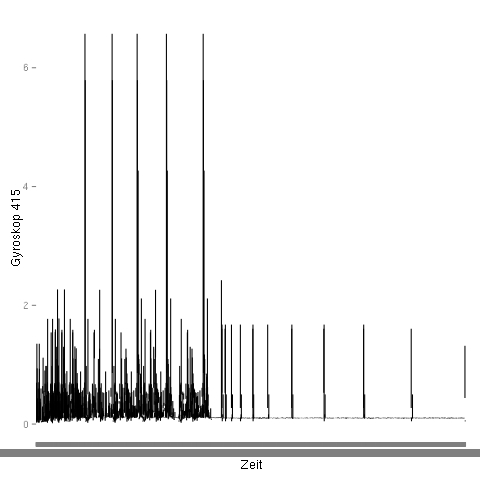

Hardware artifacts

All the sensors in our phones have typical and very unique inaccuracies. In the gyroscope data shown at the top of the page, you see spikes that shoot out from the average pattern quite regularily. Such artifacts caused by small hardware defects are specific to a single phone and can easily be used to re-identify a phone.

No technical security

“We no longer live in a world where technology allows us to separate communications we want to protect from communications we want to exploit. Assume that anything we learn about what the NSA does today is a preview of what cybercriminals are going to do in six months to two years.”

Bruce Schneier, “NSA Hacking of Cell Phone Networks”

As Bruce Schneier points out in his post: there are more than enough hints that we should not regard our phones as private. Not only have we learned how corrosive governmental surveillance has been for a long time, there are lots of commercial offerings to breach the privacy of our communication and also tap into the other, even more telling data.

But what to do? We can’t just opt-out. For most people, not using mobile phones is not an option. And frankly: I don’t want to quit my mobile. So how should we deal with it? Well, for people like me – white, privileged, supported by a legal system providing me civil rights protection, that is more discomfort than a real threat. But for everyone else, people that can not be confident in the system to protect them, the situation is truly grim.

First, we have to show people what the data does tell about them. We have to make people understand what is happening; because most people don’t. I am frequently baffled how naive even data experts often are.

Second, as Bruce Schneier argues, we have to get NSA and other governmental agencies to use their knowledge to protect us, to patch security breaches, rather then exploit these for spying.

Third, it is more important then ever, to work and fight for a just society with very general protection of not only civil but also human rights. Adelante!