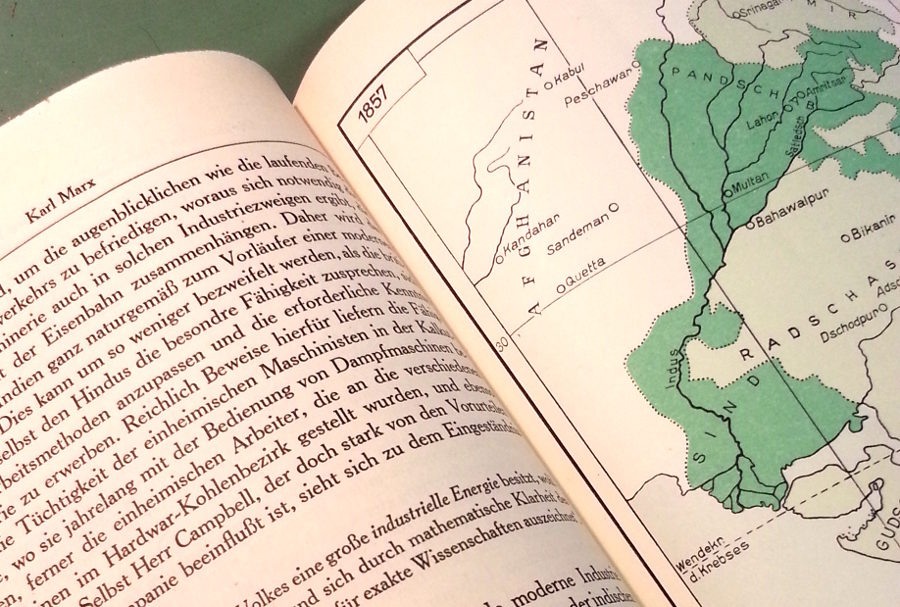

The image above is taken from “Marx Engels Werke” (MEW): Marxism is the most prominent example of what postmodernism calls a ‘Grand Narrative’. Marx and Engels took all kinds of data, drew their conclusions, and told the one story that made sense from what they found.

Un poème n’est jamais qu’un alphabet en désordre. (Jean Cocteau)

Our time is perhaps the time of an epidemic of things. (Tristan Garcia)

I remember the elderly complaining about “information over saturation” or even “overload” when I was a child, in the early 1980. 30 years later, the change of guards comes to my generation. “But once a sponge is at capacity, new information can only replace old information.” Things like that we read in random articles every day. But what is this information that people are so afraid no longer to get, when the deluge of data has taken over?

What is data? Data is the raw-content of our experience – primary the sensory readings that get conveyed into our minds, secondary the things we measure when we try to make experiences. I don’t want to get too philosophical here, but there are quite a few thinkers who share my discomfort with connecting data with facts directly. The whole postmodernism is about deconstructing false confidence with empirical truths. A century ago, Husserl already warned us, that sciences thus might give us mediated theories rather than direct evidence. Quantitative social science, be it empirical sociology, be it experimental psychology, is in particular prone to the positivist fallacy. While throwing a dice might be correctly abstracted into a series of stochastically independent occurrences of one and the same experiment, this is almost never true for human behavior.

Let us stop taking data as facts. Let us take data as fiction instead. Let us, just for the moment, think of data as the line of a story by which we tell about our experience. There might very well be no such thing like information in the data – just the scaffolding for different narratives, that reduce the randomness and complexity. Take for example how our eyes abstract the shadow in the room’s corners to straight lines that make the edges. In fact there is no such thing as a line; if you get closer and closer to the edge, you see a rather round or uneven surface spanning between one wall and the adjoining next wall. The edge-impression is just our way to reduce our visual sensory input to a meaningful aggregate; a story.

Data as such is mostly incomprehensible. To comprehend, we have to find structure, construct causalities, reduce complexity. Data visualization is fulfilling the same task: Info graphics tell a plausible story from data, make it digestible for our mind.

The link between data and our comprehension of reality from the data is built via metaphors. A metaphor connects different things in a way, we can identify one with the other. If we summarize objects under one category, this category becomes in fact the metaphor. “‘Table’ is a word with five letters”, as Rudolph Carnap put it. The concept of a ‘table’ however is the metaphor, the image, the ideal of an arbitrary set of objects. To speak of a ‘table’ is our way to evoke an image of the concrete object we have in mind in the consciousness of our audience.

There is no law that forces us to see data as necessary, as caused, and effecting. If data would be positive, scientific progress would just be correcting errors of predecessors. But certainly this is not the case. Even what is called ‘hard science’ changes direction according to the narrative. Quantum physics was not necessary. Heisenberg’s operators are not reality in the sense that there is a factual object that changes one quantum state to the next. It is a meaningful abstraction from a reality that we cannot directly comprehend. In the same way, we may use data from social interaction, behavioral data, or economic data, and try to find a meaningful narrative to share our model of the world with others.

The narrative that we derive from data is of course by no means totally random. Of course not every narrative does fit our data points. But within our measurements, any model that does not contradict the data could be possible, and might – depending on the context – make an appropriate metaphor of our reality.

Since many narratives are possible, and a broad range of parameters can fit with our data, we should be humble when it comes to value judgements. If a decision can be justified from our data depends on the model we choose. We should be clear, that we have a choice, and that with this choice comes responsibility. We should be clear about our ethics, about the policies that guide our setting the models’ parameters. We should be aware of algorithm ethics.

We should also recognize that our data story is not free from hierarchy. It is very well possible that we impose something onto others with what is just one possible narrative; no story can be told independently from social context.

When we accept data not to be just the facts that have to add to some information, but as the hints of our story, we will be liberated from the preassure of sucking every bit in our brains. We might miss something, but that will hardly be more dramatic than in past times. Our model might not be perfect, but nevertheless, in hearing the data narrative we might catch a glimpse of what is missing. We should just let go our dogma of data as facts.

As big data becomes the ruling paradigm of empirical sciences, I hope we will see lots of inspiring data stories. I hope that data will transcend from facts to fiction. And I want to hear and tell the fairytale where we wake the sleeping beauty in data.

This is the summary of my talk “Data story telling: from facts to fiction” I gave at the Content Strategy Forum 2014 in Frankfurt: