Bring cutting-edge technologies and products to larger markets, making them mainstream – that’s what Moore’s Crossing the Chasm is all about. Where is this specific point in a technology’s adoption lifecycle that transforms a nerd toy into a quite natural product of everyday’s life?

The biggest, and possibly only, problem of the Quantified Self is its name: whereas “the self” is a widely known – though misunderstood – term, “quantified” is a so-called conversion: a verb turned into an adjective. Those grammatic conversions require additional thought processes before people either express them or understand them. Second, “quantified” is a foreign word which we all would not use every day.

It must be assumed that, when Kevin Kelly and Gary Wolf started the Quantified Self movement in 2007, agreeing upon this term did not come easy, although it exactly defines itself: an [international] collaboration of users and makers of self-tracking tools. In this definition, the difference between Quantified Self and self-tracking becomes evident: whereas self-tracking describes the individual (and detached) behavior of collecting data about oneself, the Quantified Self additionally contains the aspect of collaboration of individuals and/or groups of self-trackers. So – it seems to be difficult or even impossible to ease the way for the Quantified Self by renaming it self-tracking.

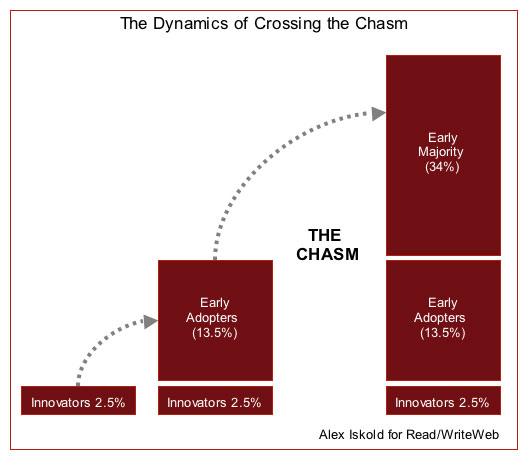

But, let’s put the wording problem aside for a moment, and let’s take a look at the hurdles technologies have to overcome on their way to mass market. Alex Iskold from RRW describes the dynamics:

To become a mass market product, it has to attract Innovators, which typically are defined as 2.5% of the market, followed by the Early Adopters, which make up for 13.5%. After used by around 16% of the market, a chasm yawns. To become mainstream, the product has to motivate the next group, the 34% Early Majority, to be used by up to 50% of the market.

Compared with 1991, when Geoffrey A. Moore introduced the term “Crossing the Chasm”, the speed of new market entrants has increased dramatically. Many technologies – especially those invented in Silicon Valley – are aimed at innovators and early adopters. And 12 months after a product has gained traction, it’s online at amazon.com or the Apple Store, and that means a worldwide availability. Today, startups can sell their products in the tens of thousands in a foreign market before they even have their first customer support agent hired – a typical early adopter’s problem.

In the U.S., retailers like Safeway, mobile operators and others have shelves offering fitness gear communicating with apps – the most visible quantified self products these days. According to Pew Internet, 66% of North Americans track themselves with dedicated devices and 46% state that they have changed their behavior based on the collected data. What Pew does not disclose is whether those people actually know that their behavior is called Quantified Self. It’s a matter of fact: more and more people who quantify themselves haven’t heard of that specific term before. They just do it. The reason: there are no “Quantified Self” signs at the shelves. People buy wristbands or smart watches, but not “quantified self” tools.

Coming back to wording: if “the Quantified Self” will be used as a more academic term for people buying wristbands, smart watches, smart clothes, etc., and sharing their data, then we’ll have the interesting effect of a coming mass market with a name only insiders know about.

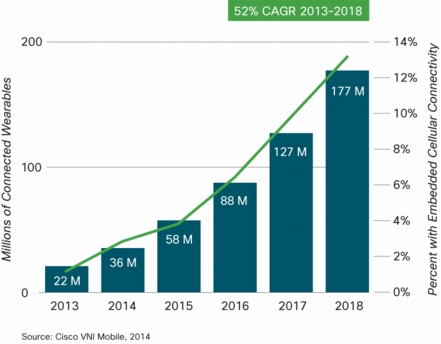

Did I say mass market? Indeed: ask the one market research company or another, the market for so-called wearable tech; i.e. the technology used by the Quantified Self – will grow to $30-40 billion in 2018. I call that a mass market. The assumption behind these numbers – as always – is that these products cross the chasm, that they overcome the hurdle from motivating early adopters only to wow the early majority, too.

In our opinion, that’s possible. Why? The Quantified Self / Wearable Tech will become a huge market because it empowers the individual: QS redirects competences from experts – physicists, scientists, etc. – to the individual. Sue Clark is able to collect and analyze enough high quality data to be informed about her health situation at all times. She can either predict serious health problems like strokes, or she can help to prevent them by changing her behavior to the better. QS gives autonomy back to the individual, and this is the main force behind a dynamic growth of this market.

The growth rates will depend on the availability, the usability and the personalization of advice – aka social relevance:

- Everybody must be able to use the device. The device itself should be free or cost less than $100.

- It must be absolutely easy to use the device – nobody must be overly creative or be urged to engage heavily.

- The user must get individual and personalized recommendations to change her behavior, if necessary. No standardized programs, but individual advice.

If these criteria are met, a QS device, be it a wearable app, or hardware, will be sold in its tens or hundreds of thousands within short notice. And problems like obesity, which alone costs the United States more than $150 billion in lost productivity a year, could be addressed in a new way.

And then, the Quantified Self will have crossed the chasm – perhaps without even being noticed.